Le Voyage du Horla

J'avais reçu, dans la matinée du 8 juillet, le télégramme que voici: 'Beau temps. Toujours mes prédictions. Frontières belges. Départ du matériel et du personnel à midi, au siège social. Commencement des manoeuvres à trois heures. Ainsi donc je vous attends à l'usine à partir de cinq heures. JOVIS.

'A cinq heures précises, j'entrais à l'usine à gaz de La Villette. On dirait les ruines colossales d'une ville de cyclopes. D'énormes et sombres avenues s'ouvrent entre les lourds gazomètres alignés l'un derrière l'autre, pareils à des colonnes monstrueuses, tronquées, inégalement hautes et qui portaient sans doute, autrefois, quelque effrayant édifice de fer.

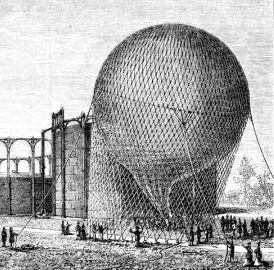

Dans la cour d'entrée, gît le ballon, une grande galette de toile jaune, aplatie à terre, sous un filet. On appelle cela la mise en épervier; et il a l'air, en effet, d'un vaste poisson pris et mort.

Deux ou trois cents personnes le regardent, assises ou debout, ou bien examinent la nacelle, un joli panier carré, un panier à chair humaine qui porte sur son flanc, en lettres d'or, dans une plaque d'acajou: Le Horla.

On se précipite soudain, car le gaz pénètre enfin dans le ballon par un long tube de toile jaune qui rampe sur le sol, se gonfle, palpite comme un ver démesuré. Mais une autre pensée, une autre image frappent tous les yeux et tous les esprits. C'est ainsi que la nature elle-même nourrit les êtres jusqu'à leur naissance. La bête qui s'envolera tout à l'heure commence à se soulever, et les aides du capitaine Jovis, à mesure que Le Horla grossit, étendent et mettent en place le filet qui le couvre, de façon à ce que la pression soit bien régulière et également répartie sur tous le points.

Cette opération est fort délicate et fort importante; car la résistance de la toile de coton, si mince, dont est fait l'aérostat, est calculée en raison de l'étendue du contact de cette toile avec le filet aux mailles serrées qui portera la nacelle.

Le Horla, d'ailleurs, a été dessiné par M. Mallet, construit sous ses yeux et par lui. Tout a été fait dans les ateliers de M. Jovis, par le personnel actif de la société, et rien au dehors.

Ajoutons que tout est nouveau dans ce ballon, depuis le vernis jusqu'à la soupape, ces deux choses essentielles de l'aérostation. Il doit rendre la toile impénétrable au gaz, comme les flancs d'un navire sont impénétrables à l'eau. Les anciens vernis à base d'huile de lin avaient le double inconvénient de fermenter et de brûler la toile qui, en peu de temps, se déchirait comme du papier.

Les soupapes offraient ce danger de se refermer imparfaitement dès qu'elles avaient été ouvertes et qu'était brisé l'enduit, dit cataplasme, dont on les garnissait. La chute de M. Lhoste, en pleine mer et en pleine nuit, a prouvé, l'autre semaine, l'imperfection du vieux système.

On peut dire que les deux découvertes du capitaine Jovis, celle du vernis principalement, sont d'une valeur inestimable pour l'aérostation.

On en parle d'ailleurs dans la foule, et des hommes, qui semblent être des spécialistes, affirment avec autorité que nous serons retombés avant les fortifications. Beaucoup d'autres choses encore sont blâmées dans ce ballon d'un nouveau type que nous allons expérimenter avec tant de bonheur et de succès.

Il grossit toujours, lentement. On y découvre de petites déchirures faites pendant le transport; et on les bouche, selon l'usage, avec des morceaux de journal appliqués sur la toile en les mouillant. Ce procédé d'obstruction inquiète et émeut le public.

Pendant que le capitaine Jovis et son personnel s'occupent des derniers détails, les voyageurs vont dîner à la cantine de l'usine à gaz, selon la coutume établie.

Quand nous ressortons, l'aérostat se balance, énorme et transparent, prodigieux fruit d'or, poire fantastique que mûrissent encore, en la couvrant de feu, les derniers rayons du soleil.

Voici qu'on attache la nacelle, qu'on apporte les baromètres, la sirène que nous ferons gémir et mugir dans la nuit, les deux trompes aussi, et les provisions de bouche, les pardessus, tout le petit matériel que peut contenir, avec les hommes, ce panier volant.

Comme le vent pousse le ballon sur les gazomètres, on doit à plusieurs reprises l'en éloigner pour éviter un accident au départ.

Tout à coup le capitaine Jovis appelle les passagers.

Le lieutenant Mallet grimpe d'abord dans le filet aérien entre la nacelle et l'aérostat, d'où il surveillera, durant toute la nuit, la marche du Horla à travers le ciel, comme l'officier de quart, debout sur la passerelle, surveille la marche du navire.

M. Etienne Beer monte ensuite, puis M. Paul Bessand, puis M. Patrice Eyriès, et puis moi.

Mais l'aérostat est trop chargé pour la longue traversée que nous devons entreprendre, et M. Eyriès doit, non sans grand regret, quitter sa place.

M. Jovis, debout sur le bord de la nacelle, prie, en termes fort galants, les dames de s'écarter un peu, car il craint, en s'élevant, de jeter du sable sur leurs chapeaux; puis il commande: 'Lâchez-tout! ' et tranchant d'un coup de couteau les cordes qui suspendent autour de nous le lest accessoire qui nous retient à terre; il donne au Horla sa liberté.

En une seconde nous sommes partis. On ne sent rien; on flotte, on monte, on vole, on plane. Nos amis crient et applaudissent, nous ne les entendons presque plus; nous ne les voyons qu'à peine. Nous sommes déjà si loin! si haut! Quoi! nous venons de quitter ces gens là -bas? Est-ce possible? Sous nous maintenant, Paris s'étale, une plaque sombre, bleuâtre, hachée par les rues, et d'où s'élancent de place en place, des dômes, des tours, des flèches; puis, tout autour, la plaine, la terre que découpent les routes longues, minces et blanches au milieu des champs verts, d'un vert tendre ou foncé, et des bois presque noirs.

La Seine semble un gros serpent roulé, couché immobile, dont on n'aperçoit ni la tête ni la queue; elle vient de là -bas, elle s'en va là -bas, en traversant Paris, et la terre entière a l'air d'une immense cuvette de prés et de forêts qu'enferme à l'horizon une montagne basse, lointaine et circulaire.

Le soleil qu'on n'apercevait plus d'en bas reparaît pour nous, comme s'il se levait de nouveau, et notre ballon lui-même s'allume dans cette clarté; il doit paraître un astre à ceux qui nous regardent. M. Mallet, de seconde en seconde, jette dans le vide une feuille de papier à cigarettes et dit tranquillement: 'Nous montons, nous montons toujours', tandis que le capitaine Jovis, rayonnant de joie, se frotte les mains en répétant: 'Hein? ce vernis, hein! ce vernis.

'On ne peut, en effet, apprécier les montées et les descentes qu'en jetant de temps en temps une feuille de papier à cigarettes. Si ce papier, qui demeure, en réalité, suspendu dans l'air, semble tomber comme une pierre, c'est que le ballon monte; s'il semble au contraire s'envoler au ciel, c'est que le ballon descend.

Les deux baromètres indiquent cinq cents mètres environ, et nous regardons, avec une admiration enthousiaste, cette terre que nous quittons, à laquelle nous ne tenons plus par rien et qui a l'air d'une carte de géographie peinte, d'un plan démesuré de province. Toutes ses rumeurs cependant nous arrivent distinctes, étrangement reconnaissables. On entend surtout le bruit des roues sur les routes, le claquement des fouets, le 'hue' des charretier, le roulement et le sifflement des trains, et les rires des gamins qui courent et jouent sur les places. Chaque fois que nous passons sur un village, ce sont des clameurs enfantines qui dominent tout et montent dans le ciel avec le plus d'acuité.

Des hommes nous appellent; des locomotives sifflent; nous répondons avec la sirène qui pousse des gémissements plaintifs, affreux, maigres, vraie voix d'être fantastique errant autour du monde;

Des lumières s'allument de place en place, feux isolés dans les fermes, chapelet de gaz dans les villes. Nous allons vers le nord-ouest après avoir plané longtemps sur le petit lac d'Enghien. Une rivière apparaît: c'est l'Oise. Alors nous discutons pour savoir où nous sommes. Cette ville qui brille là -bas, est-ce Creil ou Pontoise? Si nous étions sur Pontoise, on verrait semble-t-il la jonction de la Seine et de l'Oise; et puis ce feu, cet énorme feu sur la gauche, n'est-ce pas le haut fourneau de Montataire?

Nous nous trouvons en vérité sur Creil. Le spectacle est surprenant; sur la terre, il fait nuit et nous sommes encore dans la lumière, à dix heures passées. Maintenant nous entendons les bruits légers des champs, le double cri des cailles surtout, puis les miaulements des chats et les hurlements des chiens. Certes, les chiens sentent le ballon, le voient et donnent l'alarme. On les entend, par toute la plaine, aboyer contre nous et gémir, comme ils gémissent à la lune. Les boeuf aussi semblent se réveiller dans les étables, car ils mugissent; toutes les bêtes effrayées s'émeuvent devant ce monstre aérien qui passe.

Et les odeurs du sol montent vers nous délicieuses, odeurs des foins, des fleurs, de la terre verte et mouillée, parfumant l'air, un air léger, si léger, si doux, si savoureux que jamais de ma vie je n'avais respiré avec tant de bonheur. Un bien-être profond, inconnu, m'envahit, bien-être du corps et de l'esprit, fait de nonchalance, de repos infini, d'oubli, d'indifférence à tout et de cette sensation nouvelle de traverser l'espace sans rien sentir de ce qui rend insupportable le mouvement, sans bruit, sans secousses et sans trépidations.

Tantôt nous montons et tantôt nous descendons. De minute en minute, le lieutenant Mallet, suspendu dans sa toile d'araignée, dit au capitaine Jovis: 'Nous descendons, jetez une demi-poignée. ' Et le capitaine, qui cause et rit avec nous, un sac de lest entre ses genoux, prend dans ce sac un peu de sable et le jette par-dessus bord.

238

I had received, during the morning of July 8, the following telegram: nice weather.

My predictions still.

Belgium frontier.

headquarters

Departure of material and personnel at noon, at the headquarters.

Beginning of maneuvers at three o'clock.

Therefore I wait for you at the factory beginning at five o'clock.

JOVIS.

At five o'clock exactly, I was entering the gas factory of La Villette.

ruine ruin

One would say (it seems like) the colossal ruins of a city of Cyclopes.

gazomètre gas meter

columns

Enormous and dark avenues open up between heavy gas meters lined up one behind the other, similar to monstrous columns, truncated, unequally high and that carried without doubt, at another time, some scary structure of iron.

gésir to lie

cake

aplatir to flatten

net

canvas

In the entry courtyard, lies the balloon, a large cake of yellow fabric, flattened on the ground, under a net.

and it appears, in fact, like a vast fish, caught and dead.

Two or three hundred people look at it, sitting or standing, or instead examine the gondola, a pretty square basket, a basket the color of human flesh that carries on its side, in golden letters, on a black mahogany plaque: Le Horla.

basket/gondola

One hurries now, because the gas enters finally into the balloon by a long tube of yellow material that slides on the ground, swells up, twitches like an over-sized worm.

The beast that will fly soon begins to rise up, and the assistants of the captain Jovis, as the Horla enlarges, extend and put in place the net that covers it, in such a way that the pressure is regular and equally distributed to all points.

But another thought, another image strikes everyone's eyes and everyone's mind.

It is this way that nature itself nourishes beings until their birth.

The Horla, by the way, was designed by Monsieur Mallet, constructed under his eyes and by him.

because the resistance of the cotton fabric, so thin, of which the aerostat is made is calculated as a function of the amount of contact of this material with the thin net that will carry the gondola.

Everything was made in the workshops of Monsieur Jovis, by the staff of the company, and nothing outside.

workshops

basket

flesh

flank

mahogany

(adjective) square

golden letters

sparrowhawk

entry courtyard

One must add that everything is new in this balloon, from the varnish to the valve, those two essential things of the aerostation.

It must render the fabric impenetrable to the gas, like the sides of a boat are impenetrable to water.

The old varnishes based on flax oil had the double unsuitability of fermenting and of burning the fabric which, in little time, tore apart like paper.

The valves offered this danger of closing up imperfectly soon as they had been opened and the coating, thats to say the poultice, which they had applied was broken.

The fall of Monsieur Lhoste, in the middle of the sea and the middle of the night, prouved, the other week, the imperfection of the old system.

One could say that the two discoveries of the Captain Jovis, that of the varnish principally, are of inestimable value to the aerostation.

It was spoken about in addition in the crowd, and men, that seemed to be specialists, affirmed with authority that we will have fallen before the fortifications.

Many other things even are criticized in this balloon of a new type which we will experience with such pleasure and success.

It's still growing, slowly.

This procedure of blocking disquiets and moves the public.

This operation is very delicate and very important;

One calls this the conversion into sparrowhawk;

Small tears are discovered on it made during its transport;

and they were clogged, according to the practice, with pieces of moistened newspaper applied to the fabric.

While the Captain Jovis and his personnel occupy themselves with the last details, the voyagers are going to dine at the cafeteria of the gas factory, according to the established custom.

When we exit again, the aerostat is swaying, enormous and transparent, prodigious fruit of gold, fantastic pear that the last rays of the sun still ripen covering it with fire.

It is here that the gondola is attached, that the barometers are carried over, the siren that will make us moan and wail in the night, the two horns also, and the eating provisions, the overcoat, all the material that can contain, with the men, this flying basket.

As the wind pushes the ballon on to the gas meters, it must be distanced several times from it inorder to avoid an accident at departure.

All of a suddent Captain Jovis calles the passengers.

The Lieutenant Mallet climbs first into the aerial net between the gondola and the aerostat, from where he will survey, during all the night, the progress of the Horla across the sky, like the watch officer, standing on the gangway, surveys the progress of the ship.

Monsieur Etienne Beer climbs up next, then M. Paul Bessand, then Monsieur Patrice Eyriès, and then me.

But the aerostat is too loaded for the long crossing that we must start, and Monsieur Eyriès must, not without much regret, leave his place.

Monsieur Jovis, standing on the edge of the gondola, asks, in very gallant terms, the ladies to separate themselves away a little, because he fears, on rising up, of throwing sand onto their hats;

then he orders: "Release everything!"

he gives to the Horla its liberty.

And cutting with a strike of a knife the ropes that hang around us the incidental ballast that keeps us on the ground;

In a second we are departed.

One doesn't feel anything;

you float, you rise, you fly, you glide.

Our friends shout and applaud, we hardly hear them anymore;

we only barely see them.

So high!

What!

We just left those people over there?

Is it possible?

Under us now, Paris extends, a dark blotch, bluish, cut up by the streets, and from where jumps up in various places, domes, towers, steeples;

then, all around, the plain, the land that cuts up the long roads, thin and white in the middle of green fields, of a soft or dark green, and woods almost black.

The Seine seems to be a large coiled up serpent, laying down immobile, of which one did not perceive neither the head or the tail;

it comes from over there, it leaves over there, crossing Paris, and the entire land seems to be an immense basin of meadows and forests that a low mountain on the horizon, distant and circular, closes up.

The sun that one did not notice anymore from below reappears for us, as if it rose up again, and our balloon itself lights up in this light;

it must seem like a star to those that look at us.

Monsieur Mallet, from second to second, throws into the void a piece of cigarette paper and says tranquilly;

we rise up, we rise up still, while Captain Jovis, beaming with joy, rubs his hands together repeating:

Eh?

This varnish, eh!

this varnish.

One cannot, in fact, assess the climbs and the descents but by throwing out from time to time a piece of cigarette paper.

If this paper, that remains, in reality, suspended in the air, seems to fall like a rock, it is that the balloon climbs;

if it seems on the contrary to fly off toward the sky, it is that the balloon descends.

The two barometers indicate about five hundred meters, and we look at with an enthusiastic admiration, this land that we leave, to which we are not connected at all by anything and that seems to be a painted map of geography, of a oversized map of Province.

All these soft noises reach us distinct, strangely recognizable.

You hear especially the noise of wheels on the roads, the cracking of whips, the 'yaw' of stagecoach drivers, the rolling and the whistling of trains, the laughs of kids that run and play in the town squares.

Every time we pass over a village, it is the roar of children that dominates everything and climbs into the sky with the most acuteness.

Men call to us;

locomotives whistle;

we respond with a siren that puts out plaintive groans, frightening, thin, true voice of a fantastic being roaming around the world.

Lights come on from various places, isolated fires on the farms, chimneys of gas in the towns.

We are going toward the northwest after having glided for much time over the small lake of Enghien.

A river appears: it is the Oise.

Now we discuss with each other in order to find out where we are.

That town that shines over there, is it Creil or Pontoise?

and then this fire, this enormous fire over to the left, is it not the furnace of Montataire?

If we were over Pontoise, one would be able to see it seems the junction of the Seine and of the Oise;

We are located in truth over Creil.

The spectacle is surprising;

on the ground it is night and we are still in the light, past ten o'clock.

Now we hear the soft noises of the fields, the double cry of quails especially, then the meowing of cats and the howling of dogs.

Certainly, the dogs smell the balloon, see it and give the alarm.

You hear them all over the plain, barking at us and howling, like they howl to the moon.

The cows also seem to wake up in the stables because they moo;

all the scared animals become worked up before this aerial monster that passes.

And the smells of the ground climb toward us, delicious, smells of hay, of flowers, of the green and wet land, perfuming the air, the light air, so light, so sweet, so delicious that never in my life have I breathed with so much happiness.

A profound well-being, unknown, invades me, well-being of body and of mind, made from non-caring, of infinite rest, of forgetting, of indifference to everything and of this new sensation of traversing space without feeling anything that which makes movement insupportable, without noise, without jolts and without trepidations.

Sometimes we climb and sometimes we descend.

From time to time, the Lieutenant Mallet, suspended in his spider web, says to Captain Jovis: we are descending, throw out half a fistful.

And the captain who converses and laughs with us, a sack of ballast between his knees, takes from the sack a little sand and throws it over the edge.

hay

smells

made from a lack of caring/worrying

Elle marche, elle parle avec nonchalance, avec une certaine nonchalance qui nâest pas sans grâce.

She walks, she talks without a care, with a certain nonchalance that is not without grace.

rest

Il y a longtemps que vous travaillez, donnez-vous un peu de repos

You've been working for a long time ago give yourself a little rest.

infinite

forgetting

jolts

trepidation / fear

well-being

sometimes

causer converse

throw overboard

Il sauta par-dessus la barrière.

He jumped over the fence.

Il porte un grand manteau par-dessus son habit.

He wears a cloak over his clothes.

Le bord de lâeau.

The edge of the water.

ballast

(Action de mettre)

Mise en bouteilles - bottling

Mise en marche - start in motion

Mise en bière - conversion into beer

Mise au point - update

Mise en valeur- enhance the value

Action de mettre

Mise en bouteilles to bottle

Mise en marche to start in motion

Mise en bière -

Mise au point -

Mise en valeur -

structure

scary

truncated

monstrous

city of cyclopes (giant one-eyed people)

dark

ramper to crawl; to slide on the ground

Le serpent et le ver de terre rampent sur le sol.

The snake and the worm craw on the ground.

sitting

asseoir - to sitAsseyons-nous par terre.

Let us sit on the floor.

standing

porter- to bear, to carryCe monument porte telle inscription.

this monument bears this inscription.

se précipiter - to hurry

canvas

palpiter to twitch; to beat

en-dehors de la terre, le ver palpite

outside of the earth, the worm beats

enormous

gonfler to swell

Le vent gonfle les voiles.

the wind fills the sails.

thought

frapper strike

birth

to lift up slightly

grossir grows

répartir to distribute

La mère a reparti le gâteau entre ses enfants

the mother distributed the cake between her children

thin

mesh

dessiner to design, to draw

Dessiner le paysage.

draw the landscape.

employees

company

flax

oil

to ferment

varnish

varnish

pénetrer to penetrate

envoler take off

Le moindre bruit fait envoler les moineaux.

The slightest noise makes the sparrows fly off.

étendre - to spread out, to stretch

Lâarmée sâétendit dans la plaine.

The army spread out in the plain.

Ãtendre le bras

streatch out the arm

balloon

valve

(Art de construire des aérostats, de les employer, de les diriger)

art of building airships, their use, and piloting

déchirer to tear

1.) coating

Un enduit de goudron a coating of tar

2. (Couche de chaux, de plâtre, de ciment, ou de quelque autre matière semblable, que lâon applique sur les murailles) layer of lime, plaster, cement, or some similar material that is applied on the walls.

(Une préparation de plante assez pâteuse pour être appliquée sur la peau dans un but thérapeutique.)

a preparation of plants to be applied on the skin for therapeutic purposes.

garnir - garnish

Garnir une bibliothèque de livres

Supply a library with books

crowd

fortifications

refers to the wall built in 1840 that surrounds Paris (See Enceintes de Paris)

fortifications

refers to the wall built in 1840 that surrounds Paris (See Enceintes de Paris)

blâmer to criticize; to blame

spider web

mouiller to wet

rosary

river that flows into another river (not the sea)

blast furnace

(fourneau destiné à fondre le minerai de fer à une haute température)

furnace for melting iron ore at high temperature

junction

whimpering

plaintive

affreux / affreuse (adjective) frightening

2. ) (Sortir avec force en parlant des paroles, des sons)

speaking words or making sounds with force

Il poussait des cris.

he shrieked.

1. ) push

murmurs (wind, voice)

cracking

driver of a cart

rolling

whistle

cacophony

demeurer to remain

Il a demeuré trois ans à Paris.

he stayed three years in Paris.

Demeurer à son poste.

Stay at his post.

cafeteria

boucher to stop up

newspaper

emouvoir (

Provoquer une émotion.) provoke an emotionIl sâémeut à la vue de la souffrance.

He is moved at the sight of suffering.

balancer to sway, to swing

Balancer ses bras. Swing his arms

ressortir go out again

prodigieux / prodigieuse marvelous, stupendous

pear

mûrir to ripen

rays

barometers

siren, (boat) foghorn

to moan

to wail

horns

supplies of food

overcoats

watch officer

bridge

to undertake

prier to request

écarter - to move something further apart

Le vent a écarté les nuages.

the wind moved the clouds away from each other.

trancher cut through

ropes

map

star

void

frotter - to rub

planer to glide

étaler - to spread out

bluish

chopped

bowl

meadows

meows

howling

quails

sentir to smell

plant, factory

briser to break

fall

custom, habit

Il a lâusage de dîner de bonne heure.

he has the habit of having dinner early.

briller to shine

commander to order